Why is it so hard to make housing in Australia affordable?

With a Federal election around the corner both major parties policies focus so much on more demand supporting higher prices, why can't prices just fall?

For full disclosure, as I write this article I own a house which I purchased in 2021 I own less of it than the bank does but the value of my property has increased significantly since it has been purchased. I have in the past owned investment properties but I currently don’t.

With both Labor and the Coalition recently announcing their election policies it was encouraging to see them announce some measures that focused on increasing supply but yet again both had policies which would see an increase in demand for housing and support higher property prices rather than true improvements in affordability which are brought about by lower prices.

If we want to improve housing affordability in Australia the easiest way to do so is to reduce property prices. The problem with that is that we’ve built an economy whereby the majority of our wealth is stored in housing so reducing property prices has a potentially devastating impact on the broader economy.

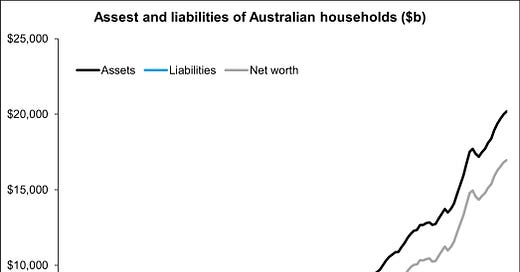

At the end of 2024, total assets of Australian households reached $20.177 trillion with total liabilities of $3.226 trillion resulting in net worth of $16.952 trillion. Australian households hold a much higher value of assets than they do liabilities, but I’ll give you one guess as to what most of those assets are.

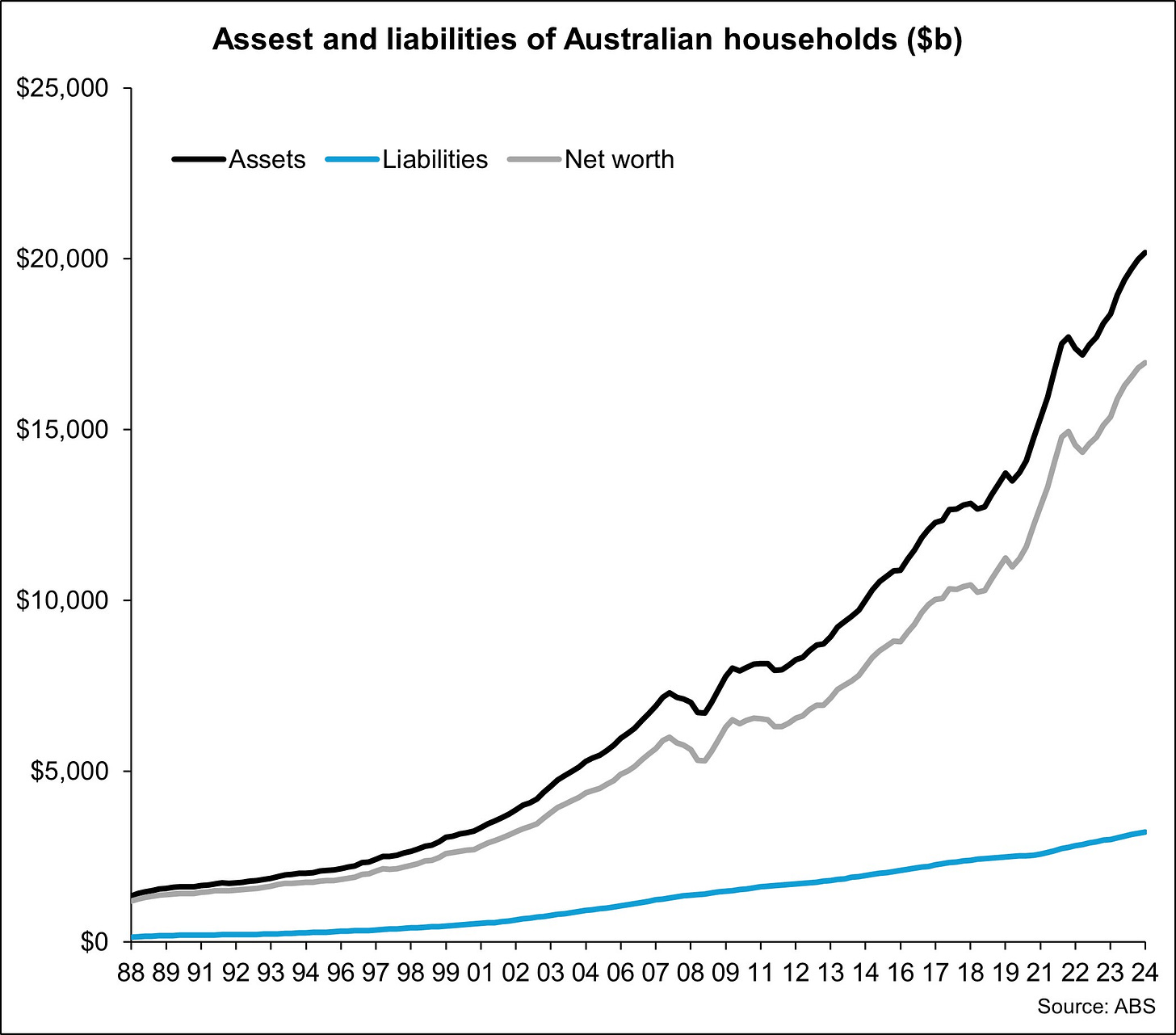

You guessed it, residential land and dwellings. At the end of 2024, the total value of residential land and dwellings owned by households was $10.598 trillion which was split between $3.1254 trillion in dwellings (29.5%) and $7.475 trillion in residential land (70.5%). Residential land and dwellings accounted for 52.5% of total household assets and 66.1% (almost two-thirds) of total household assets if you exclude superannuation.

In the five years to Dec 24 alone, the total value of residential land and dwellings has increased by 54.8%. In the same five year period growth in total household assets was 46.9% and growth in household net worth was 50.8% highlighting that the increase in residential land and dwelling values drove the growth in household assets and household net worth.

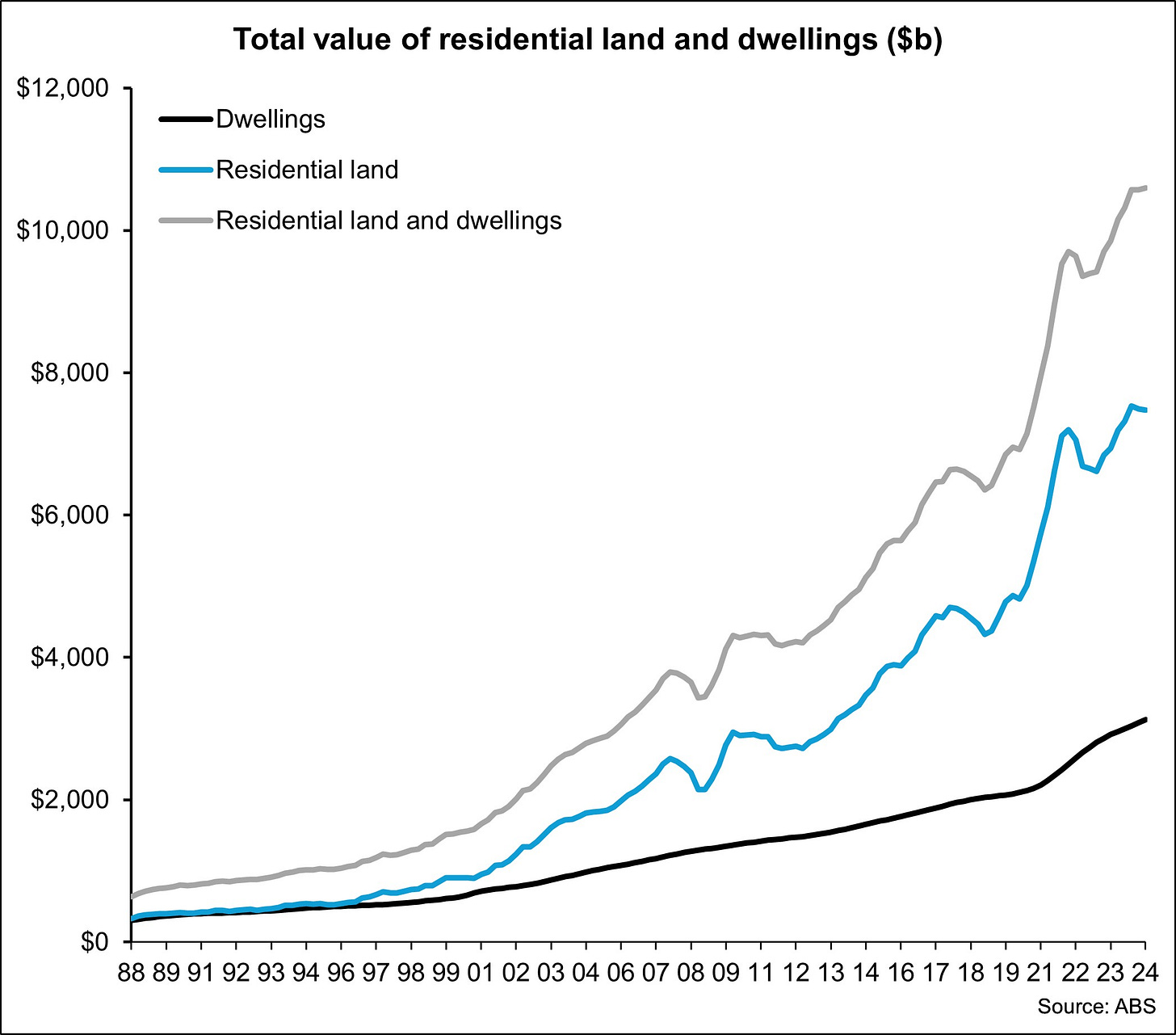

If we look at the major components of household assets between dwellings, currency and deposits, shares and other equity, superannuation and residential land these five assets account for 89.9% of the total value of household assets. Over time the share of assets in residential land and superannuation has been trending higher while the value of dwellings has trended lower and currency and deposits and shares and other equity have been relatively flat.

As at Dec 24, residential land accounted for 37% of total household assets, superannuation was 20.5%, dwellings were 15.5%, currency and deposits were 9.1% and shares and other equity were 7.8%. More than one third of household assets sits in residential land which is up from 34.7% a decade ago, 34.3% 20 years ago and 26.7% 30 years ago.

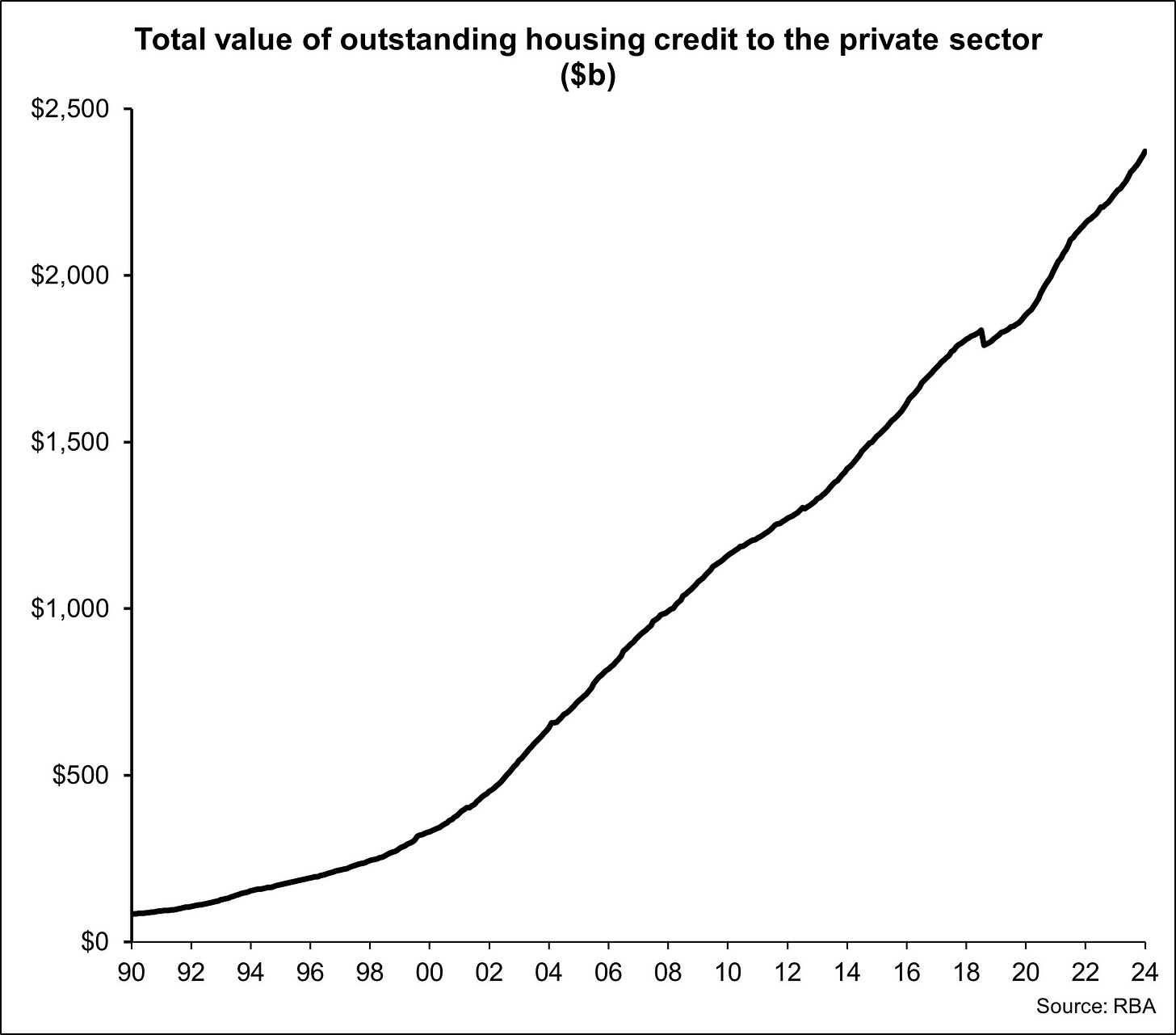

The ABS finance and wealth data which is where all of the above chart data has been pulled from doesn't have detail on liabilities for residential land and dwellings, rather it just has liabilities for loans and placements at $3.049 trillion. However, the Reserve Bank (RBA) publishes outstanding housing credit data to the private sector which should serve as a strong proxy.

At the end of 2024, the total value of outstanding housing credit to the private sector was $2.372 billion.

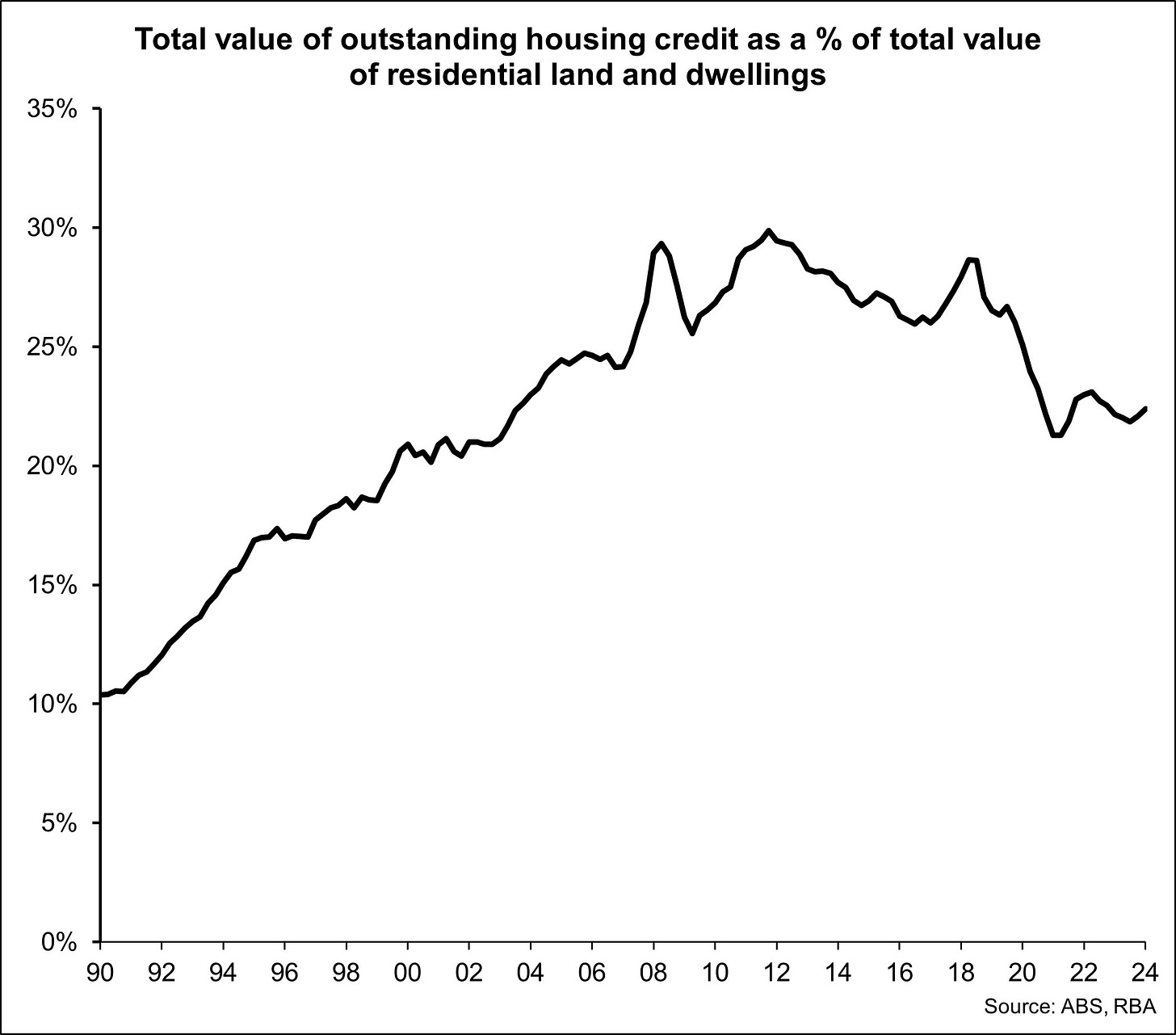

If we compare the total value of outstanding housing credit to the total value of residential land and dwellings we find that the ratio of debt to value is only 22.4% meaning that most (not all) property owners are sitting on an asset which is worth significantly more than the amount of debt they have against it. Recent buyers and those that have purchased in areas that have seen price falls or stagnant growth are obviously not in such a strong position, equally the Census tells us that 31% of households have no mortgage debt at all.

Furthermore, we can see from the previous charts that the main driver of the increase in the value of residential land and dwellings is the land value rather than the dwelling value.

This is ultimately the crux of the issue of attempting to make housing more affordable in Australia. Most of the housing in Australia are houses which have a larger land component than medium and high density housing and for many decades buying a house and holding it for a long period of time has increased the wealth of households.

Of course, housing wealth is only paper wealth because when you are trading homes, the value of your property may have increased but the value of the next property you wish to purchase has also increased so you have to take on more debt unless you are downsizing. There is a lot you can do with the equity in your residential property though such as reinvest in housing or invest in other asset classes.

Cheaper housing in Australia would largely benefit those people that don’t already own a home but aspire to purchase one and here’s where the politics of this is difficult. In 2024 the average ago of a first home buyer was approximately 36 years old. According to population data from the ABS for Sep 24, there were an estimated 6,952,318 persons in Australia between 18 and 36 (voting age) and there were 14,122,031 persons aged 37 to 100 plus. Importantly not everyone that is a resident can vote but this is a good proxy.

Given the average ago of a first home buyer is 36 years of age, you have around 33% of the population that votes that would benefit from lower property prices and 66% that wouldn’t. The 2021 Census also tells us that only 30.6% of the population rent so again, the share of the population that would benefit from lower property prices is much lower than the percentage that benefits from higher property prices.

So what can be done?

Politicians are not going to go against the will of the majority and this is why both major parties have said over the past year that their goal is slower property price growth and stronger wage growth to improve housing affordability. That is a great soundbite that won’t scare the majority of voters but in reality that would take decades to occur and wage growth has consistently undershot the increase in the value of residential property.

Relaxing zoning laws, particularly in inner-city and middle ring suburbs is often touted as a way forward and I agree we should allow more housing where people want to live, but there are definitely some things to be cautious of here.

If a property can only be a single dwelling currently and you upzone to allow it to now be say a three storey multi-unit dwelling, that property (the land really) is now more valuable than it used to be, so upzoning has increased its value. We’ve also seen over recent years, just because a site can be developed doesn’t mean it will be if the developer margins are too thin, the cost to develop increases rapidly or the owner thinks it would be beneficial to delay the delivery of that housing it won’t necessarily be developed.

Based on current preferences, there’s also a much more finite pool of purchasers for higher density housing than there are buyers for lower density housing. Of course this can shift over time and the high cost of a house is likely to drive more people to be accepting of living in an apartment or townhouse in a more desirable suburb rather than a detached house they simply can’t afford.

We should relax zoning laws but I doubt that alone will result in long-lasting sustained housing affordability improvement unless there is someone (like government or government in a public private partnership with developers) willing to develop throughout the housing cycle or we significantly increase and incentivise build-to-rent which is less impacted by the short term housing cycle fluctuations and not reliant on presales like traditional build to sell is. In fact, the prevalence of build-to-rent apartments in the USA is likely one the major reasons why upzoning has been so successful, here in Australia it is an asset class in its absolute infancy and to date largely targeted at higher-end rentals.

We should also make it easier for developers seeking to deliver greenfield housing to acquire approvals and we should look for ways to reduce the cost of this new housing. New homes have GST included in the cost while existing homes don’t and the cost of a new home also includes the cost of all the associated approvals and infrastructure which again a second-hand home doesn’t. These are areas the government should be thinking about to reduce the cost of new housing.

Finally the biggest change we need to see and probably the hardest to achieve is a paradigm shift whereby we don’t see investment in residential housing as the way to get wealthy because as I noted before if you are trading in the same market the next property you purchase is also more expensive.

This paradigm shift is a difficult one because the equity in our homes are often used to fund small businesses and housing has proven to be an asset class that consistently increases in value over time. Governments should be looking at ways to encourage other asset classes to invest in rather than investment in shelter.

As the headline says, it is so hard to make housing in Australia affordable and it will take a significant leap of faith by politicians and voters to change the system which encourages so much of our wealth to be tied-up in housing.

I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Thanks for the great analysis Cam. Apart from the supply issues, I think the demand side also needs to be addressed. Speaking as an immigrant myself, I don't think it's great for housing affordibility and quality of life overall to import half a million permanent residents per year, most of whom end up in Sydney or Melbourne. New immigrants should be encouraged to settle in less densely populated/regional areas. But I appreciate how politically difficult that would be for any party and politician to do.

Full marks for noticing what almost no-one does; upzoning makes "house prices" go up, not down. Every single property involved becomes a "site with redevelopment potential" and this sets its price. I have been predicting this for more than a decade; every time more upzoning is done. I predicted that NZ's draconian top-down nationally imposed upzoning circa 2020 would cause the biggest house price inflation yet. On top of an already absurd and disastrous housing affordability situation.

The only thing that changes this wicked paradigm, is liberalization of greenfields land supply, which then flips "urban" economies into a "differential rent" situation instead of an extractive monopoly one. To have differential rent rather than monopoly rent, you need the main resource to be superabundant in supply. This is how it has worked, beneficially, in all goods categories since the era of Karl Marx when he assumed all economic rent was monopoly. Transport system improvements, refrigeration and other technology, and free trade, made the important resources superabundant and the prices of everything "differentially derived" or cost-plus or "with consumer surplus". Automobility clearly did this for housing until the time came that urban planners or other regulators flipped the supply of land for housing back to monopolistic conditions.

The sheer prices paid for greenfields land that is allowed to be developed, actually makes the cost of infrastructure a sideshow. Among the very best land economics literature is from Alan W. Evans, and one of his many insights is that when land pricing is being derived by monopoly rent mechanisms, every cost input other than the land is merely a carve-out from the monopoly gain. So forcing higher payments "for infrastructure" won't make house prices go up; it will make developers bid less for the land. But the land vendors have the extractive powers that will take out any slack well-meaningly created anywhere else in the system.

This whole racket falls over the moment innovative developers are allowed to build "urban" developments on land they paid near to true rural prices for, within effective automobile accessibility to the city. The maths on this is very simple. The automobile in "exurbs" can travel at speeds that render the supply of land for "urban use" truly superabundant. There is no need and no validity of assumption of "paving over paradise" - as soon as urban land prices everywhere are rendered "differentially derived", every form of redevelopment and infill gains a massive leverage of its potential in the affordability of the finished properties. Issi Romem's research showed that in US cities where upzoning was allowed AS WELL AS unrationed greenfields development, infill and redevelopment occurs FASTER than in the cities where infill and redevelopment are assumed to be now "instead of" greenfields development. The resulting overall housing supply is some tenfold more elastic than infill and redevelopment "instead of".

Grimes and Aitken 2010 gave us the perfect one-liner in their conclusion about "instead of" urban economies: "all the profit potential from redevelopment is impounded in the rising price of sites". This is the wedge in "housing supply" that no-one has worked out how to remove - except that because it was put there by anti-sprawl regulations, presumably it could be removed by eliminating those regulations. It is perfectly possible to require the costing in of infrastructure to housing built on greenfields, and still have systemic affordability. This cost add-on is an order of magnitude smaller than the cost of site vendor monopoly rent extraction.